Wall Street, Keynes, Debt And HYDE

(Originally written in 2020)

Wall Street threw a tantrum during the pandemic, smashing piggy banks everywhere. Yet the chatter about “traditional valuations” still drones on, as if stock prices were grounded in reality. Let’s be clear: buying a microscopic slice of a corporation through the market is nothing like owning a share of Vito’s Corner Pizzeria. The beloved P/E ratio—price to earnings—has always been a hollow metric, a shiny distraction at best. And that goes for most of Wall Street’s financial ratios, which are little more than mirages conjured by creative accounting tricks designed to keep the illusion alive.

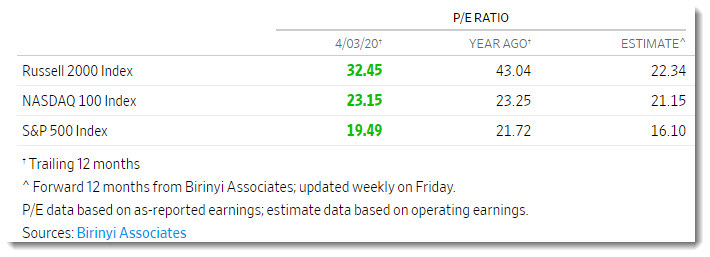

In today’s fog of uncertainty, does the S&P 500’s P/E ratio of 19.49 really capture the risk compared to last year’s 21.72? Hardly. For perspective, the lowest reading ever—5.17 in December 1917—was far closer to the reality of buying into a neighborhood diner than today’s Wall Street fantasy pricing.

If COVID‑19 taught us anything, it’s that psychology—not finance, not fundamentals—runs the show. The public never gets access to the simple, profitable tricks for riding the stock ponies, because those methods collapse under the weight of big money. If exotic quant formulas truly ruled, hedge funds wouldn’t implode, and managers wouldn’t need to skim 2% off the top while demanding 20% of profits. Remember LTCM and its army of PhDs that nearly toppled the global financial system in 1998? Proof that brilliance doesn’t equal solvency.

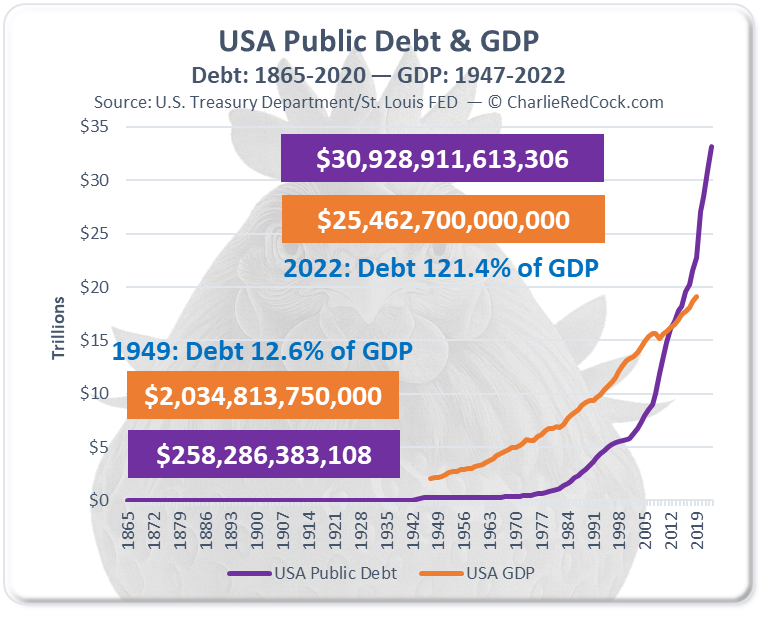

And let’s not forget: both the market and the broader economy are now paddling in a deep sea of debt, pretending the tide is under control.

Keynesian economics is the darling of politicians and Nobel Prize winners, but they only ever cook half the recipe. John Maynard Keynes himself argued for ramped‑up government spending and lower taxes to jolt demand and drag the world out of the 1930s depression—a strategy of priming the private pump with public debt.

But here’s the half everyone conveniently forgets: Keynes also expected governments to balance their books, run surpluses, and treat debt like the plague both before and after recessions. He never endorsed tossing taxpayer money into the furnace of inefficient projects. One glance at the chart “USA Public Debt & GDP” and it’s clear—John would be shaking his head in disappointment.

All debt fights for funding, and while the free market pretends to set interest rates through supply and demand, the real driver is perceived risk. That’s why credit scores exist—to shrink your identity down to a single risk number, no matter if you’re tall, short, pretty, ugly, skinny, or fat.

Then come the battles with inflation, deflation, and stagflation. Central banks juggle strategies to tame these beasts, aiming for that magical, arbitrary inflation target of 2%. Why not 3.14159%—at least then the math nerds would be happy.

In the textbook world of linear, blindfolded economics, inflation is simply “too much money chasing too few goods.” The cure? Jack up short‑term interest rates to choke demand. But here’s the obvious question: why not lower rates to boost supply instead?

Deflation flips the script—too much supply, not enough demand. Cue the central banks slashing rates to coax consumers back into the shops, even though most of that consumption is fueled by credit, which feels like an economic sin dressed up as virtue.

And then there’s stagflation, the medical emergency of economics: rising prices paired with falling jobs. Raise rates to fight inflation, and you kill employment. Lower rates to create jobs, and inflation spikes. It’s the ultimate policy pickle—no cure, just a lot of sour brine.

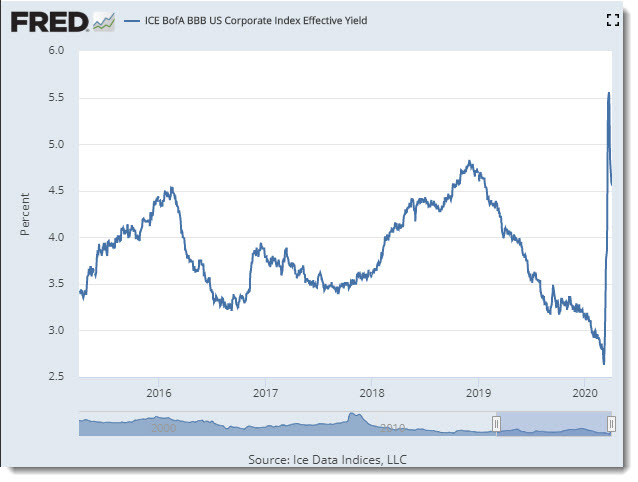

We’re staring at an economic condition with no precedent, but let’s begin with the obvious: consumer, corporate, and government debt are locked in a perpetual contest for the Guinness World Records. BlackRock’s report “Assessing Risks in the BBB‑Rated Corporate Bond Market” shines a spotlight on the weakest links—the bonds teetering just one notch above junk status, wobbling like tightrope walkers over a financial abyss.

The investment-grade corporate debt market has grown rapidly in recent years. Global capitalization reached over $10 trillion in 2019 from just over $2 trillion at the start of 2001. In the U.S., corporate debt as a percentage of GDP now stands at 47%, its highest level since 2009. At the same time, the lowest rated part of the investment-grade market has grown particularly quickly. Globally, BBB debt makes up over 50% of the market versus only 17% in 2001.

The debt situation is so precarious it’s basically a bug hunting for a windshield. How that risk translates into the “P” of the P/E ratio is anyone’s guess—it’s complicated, messy, and probably not what the textbooks promised.

The 2008 housing crisis should have been a wake‑up call, but instead it just proved how deep the love affair with debt really runs. The Federal Reserve and its battalion of economists will one day stand trial in the grand Debt Trials, but until then, everyone is stuck holding a slice of the rotting pie through pensions and retirement accounts.

The chart titled “ICE BofA BBB US Corporate Index Effective Yield” makes the point loud and clear: perceived risk has shoved BBB rates skyward, sinking investor principal faster than a NASCAR crash—without adding a dime to the coupon payments. Sure, you can hold bonds to maturity, but one default and your bird‑watching plans are toast. Once again, psychology takes the wheel: hold or sell?

All of this unfolds inside a trusted monetary system. Remove that trust, and you’re left with pure chaos. Which brings us to something worse.

Enter HYDE—High Yield in a Deflationary Environment. An economic beast we’ve never met before, born of extreme risk aversion and raw survival instinct. Creditors slam the brakes, interest rates soar, and deflation sets in because consumers retreat to buying only the bare necessities, paralyzed by fear and distrust of the future. The fallout is massive, and there’s no central bank vaccine for HYDE. Psychology trumps linear models every time. Think of it as the financial version of Mr. Hyde—ugly, unpredictable, and lurking in the shadows.