Must Elon Musk Change 'Tesla' Name To Be Next-Level?

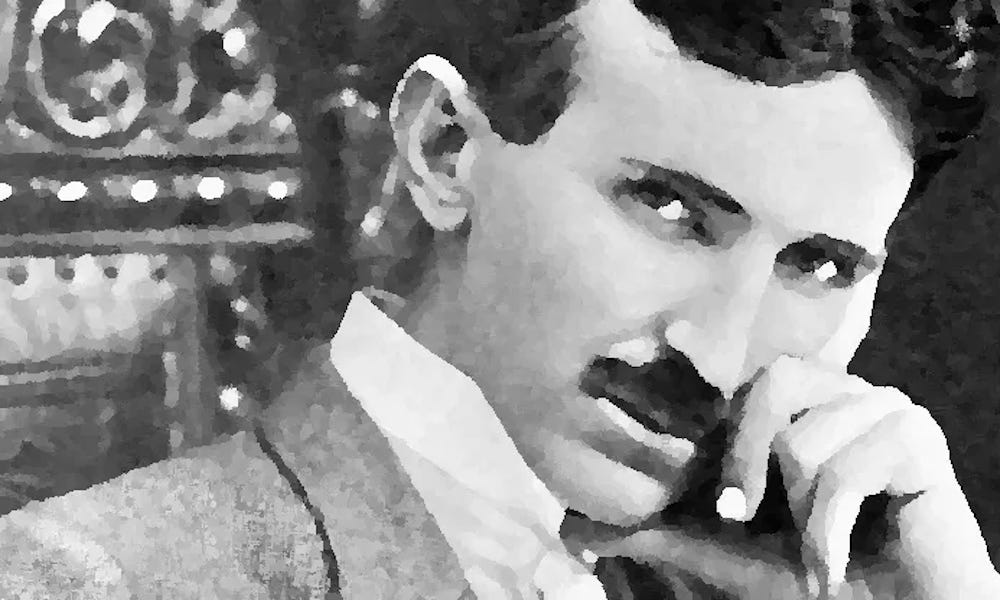

Not long ago, someone asked why the automaker chose “Tesla” as its brand name. Cue the quick history lesson: electricity, alternating versus direct current, and the already over‑worn “Edison” moniker. The answer, of course, is that Nikola Tesla lives on—despite his obscurity, especially among younger generations who spend much of their lives scrolling social feeds or camping out in line for the latest tech marvel to fill a void that never quite gets filled. Oh well, not everyone can be RedCock happy.

Meanwhile, society has developed a new pastime: purging symbols. Statues, flags, names—anything tethered to the past. We’ve reached the point where if someone is offended by something, the “threat” must be destroyed, and a safe‑space erected so certain individuals can presumably function. Beneath it all lurks a deeper stupidity, largely unnoticed or simply ignored.

My take on this newly fashionable fragile condition is simple: when someone hasn’t achieved much, it’s easier to blame others and guilt outsiders than to face reality. If you want a crash course in genuine hardship—psychological and physical—look no further than the pilgrims, staring down a do‑or‑die existence. That was struggle.

Today, however, we’re stuck in a culture of endlessly soothing feelings, a ritual designed to disguise collective failures—what I call diversity‑based whining. The result? We’re being spoon‑fed a politically correct utopia that’s less paradise and more intellectual coma. And just like that… I’ve slipped into poetry again.

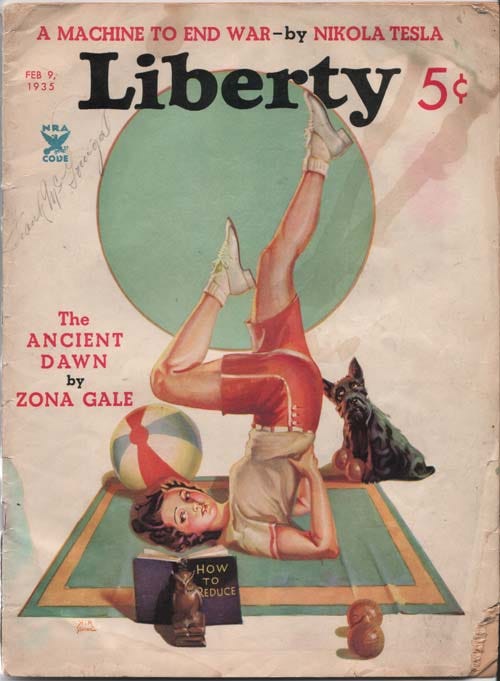

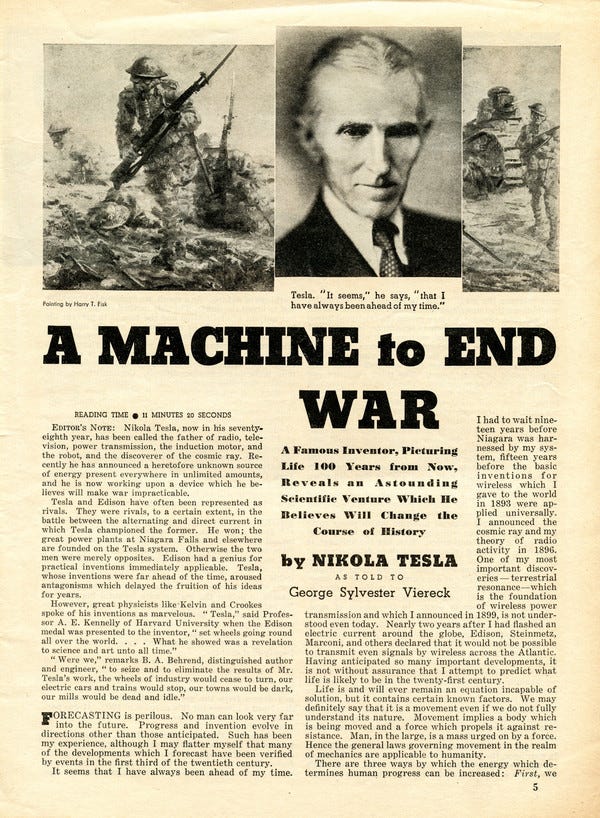

Let’s turn to Nikola Tesla—the brilliant, largely unsung figure who remains a mystery to most. His voice surfaces in the article “A Machine to End War,” shared during the Great Depression with George Sylvester Viereck, a German‑American poet and notorious propagandist. If you’re a die‑hard liberal proudly driving your eco‑friendly Tesla, the brand name might feel a little awkward once you dig into Nikola’s worldview. Yet his logic was razor‑sharp, and as inconvenient—or offensive—as it may seem, humanity will eventually catch up to it.

I often remind people: the answers are usually simple. Not the bloated stew of jargon and nonsense we’re spoon‑fed, but stark simplicity. And it’s precisely that clarity—the terrifying conclusions born of plain thought—that unsettles us most. Everyone serves a purpose, but the trouble is that not everyone likes the one they’ve been given— and that resistance often shapes the very story of their lives.

Tesla once warned that “forecasting is perilous” and “no man can look very far into the future.” Yet he still ventured a bold prediction: “in the twenty‑first century the robot will take the place which slave labor occupied in ancient civilization.” His vision of the human machine is what truly fascinates—and one might even suspect that Hitler borrowed fragments of Tesla’s thinking to fuel his own twisted blueprint.

Still, amid the darkness, Tesla offered glimmers of environmentally conscious thought—remarkable given that it was 1937. Those statements remind us that even in an age of upheaval, clarity about humanity’s relationship with nature was already surfacing.

The pollution of our beaches such as exists today around New York City will seem as unthinkable to our children and grandchildren as life without plumbing seems to us. Our water supply will he [sic] far more carefully supervised, and only a lunatic will drink unsterilized water.

Yet for all of Tesla’s unmatched brilliance, the following excerpt is the one that makes eyebrows shoot skyward—and will leave Tesla‑hugging environmentalists feeling as if they’ve been jabbed in the eye and tossed headfirst into a pit of battery acid, or crude oil if you prefer extra shock value.

The year 2100 will see eugenics universally established. In past ages, the law governing the survival of the fittest roughly weeded out the less desirable strains. Then man’s new sense of pity began to interfere with the ruthless workings of nature. As a result, we continue to keep alive and to breed the unfit. The only method compatible with our notions of civilization and the race is to prevent the breeding of the unfit by sterilization and the deliberate guidance of the mating instinct, [sic] Several European countries and a number of states of the American Union sterilize the criminal and the insane. This is not sufficient. The trend of opinion among eugenists is that we must make marriage more difficult. Certainly no one who is not a desirable parent should be permitted to produce progeny. A century from now it will no more occur to a normal person to mate with a person eugenically unfit than to marry a habitual criminal.

To sum it up: nature is ruthless, and our “new sense of pity” has preserved the “unfit”—a behavior that, sooner or later, will be corrected. Tesla hinted at this but sidestepped the uncomfortable link to sexuality, leaving us to wonder: what exactly did he mean by “unfit”? Physical weakness, intellectual deficiency, or both? Nobody really wants to walk down that road.

Here’s some food for thought: the world’s population in the 1930s hovered around 2 billion. Less than a century later, it has exploded by roughly 350%. That’s a development Tesla likely didn’t anticipate. And as always, there are pros and cons—because no matter how much we try to dress it up, we’re still animals, occasionally rational.

So let’s pause here. If anyone was searching for a safe space before, now’s the time to start digging deep in the backyard—and maybe boycott anything tied to Nikola Tesla while you’re at it: electricity, cars, cell phones. Oops, there goes social media. As for Tesla Motors, well, they might have a branding dilemma on their hands… or maybe not.