1959: The Year Economics Changed And Nobody Noticed

(Originally written in 2013)

Yes, the economy—our favorite soap opera that never gets canceled. Everyone’s still waiting for that big “turnaround episode,” but apparently all the shiny monetary gadgets, both vintage and freshly unboxed, are about as effective as a broken remote. Sure, a few jobs pop up here and there, and GDP occasionally twitches like it just heard a bad joke, but let’s be honest: the vibe is less “inspiring recovery” and more “zombie staggering toward the next cliff.”

And humanity? Oh, we’re consistent. We love reruns. We keep replaying the same mistakes like history is a sitcom we can’t stop binge-watching. Maybe it’s because history class was too boring, or maybe because we were too busy memorizing trivia like “What’s the capital of Burkina Faso?” instead of “How not to blow up the financial system… again.”

Meanwhile, Nouriel Roubini—never one to miss a chance at a catchy metaphor—served up “Bubbles in the Broth.” Because nothing says economic doom like soup imagery.

And yet, through it all, growth rates have remained stubbornly low and unemployment rates unacceptably high, partly because the increase in money supply following QE has not led to credit creation to finance private consumption or investment.

The magic phrase of the day is “finance private consumption”—because apparently the economy now runs on the idea that people should buy stuff they can’t afford, forever. It wasn’t supposed to be the plan, but hey, when has “supposed to” ever stopped us?

Sure, everyone’s heard of supply and demand. It’s the economic equivalent of “eat your vegetables”—basic, boring, and endlessly repeated. And yes, the chart that follows will dutifully show equilibrium and price discovery, like a kindergarten drawing of two lines crossing. Riveting.

But of course, there are other factors lurking in the shadows. Because if economics were just supply and demand, we wouldn’t need armies of experts, endless jargon, and Nobel Prizes for explaining why your latte costs $7.

Supply and demand can both be financed, but let’s be real: the bill always lands in demand’s lap. If a business borrows to stockpile inventory, the plan is simple—make the buyer pay for it. And if the buyer whips out a credit card, well, congratulations, they’ve just volunteered to pay twice: once for the product, and again for the privilege of debt. Equilibrium? More like a funhouse mirror, where today’s shopping spree is actually tomorrow’s headache, financed by future paychecks that haven’t even been earned yet. Let’s agree on one thing: debt was supposed to be for investment, not for buying a third air fryer.

So why 1959? That’s when credit cards with revolving credit lines showed up, and humanity collectively said, “Future me can deal with this.” Mortgages in 1934 made sense—buy a house, build a life. But by ’59, the game shifted to financing “wants” and keeping up with the Joneses, who apparently had better taste in patio furniture. The result? Every time the economy hiccups, the side effects are magnified, because humanity has the foresight of a goldfish. And no, this isn’t just an American sitcom—U.S. consumer debt became the global economy’s favorite export.

But let’s zoom out. What’s the big deal about 1959? Everyone’s still hunting for that economic crystal ball, so here’s a theory: the “Generational Economic Cycle.” It’s basically economics cosplaying as the product life cycle. Every 72 years, divided neatly into three 24-year acts, an idea or product is born, grows up, gets bloated, and then collapses under its own weight. Rinse, repeat. And yes, this applies to politics too, because everything is economics and everyone’s selling something—even hope.

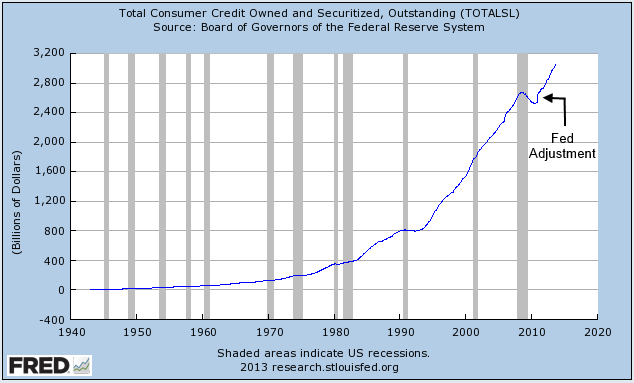

Now, about that chart from the Federal Reserve: consumer credit actually dipped during the last recession, which is about as rare as a unicorn sighting. Then, of course, it shot back up, because debt is America’s favorite hobby. And if you notice a spike, don’t worry—the Fed “adjusted” the numbers. Translation: they fiddled with the math so the graph wouldn’t look too embarrassing.

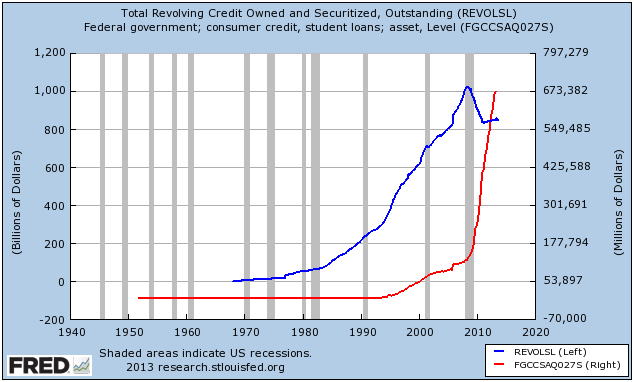

Of course, things are never quite as tidy as the textbooks promise. The chart below shows “Total Revolving Credit” (a.k.a. credit cards, humanity’s favorite magic trick) alongside student loans held by Uncle Sam. And here’s the kicker: credit cards were introduced in 1959, but the data doesn’t even bother showing up until 1968. Apparently, the first decade was just practice swiping.

By 1983—what the theory calls the “acceptance” point—Americans had racked up a cool $79 billion. Acceptance indeed: we accepted debt like it was a new religion. Fast forward to 1990, and in just seven years that number tripled to $238 billion. That’s not growth, that’s debt on steroids. And then, in December 2007, right before the economy decided to implode, we crossed the $1 trillion mark. Nothing says “holiday cheer” like a trillion-dollar credit card bill.

Plenty of folks think the credit market is bouncing back, but that’s about as believable as a diet ad. The latest Consumer Credit G.19 report shows the cracks: revolving credit (a.k.a. credit cards, the nation’s favorite hobby) slid from $1,005.2 trillion to $814.7 billion between 2008 and September 2013—a tidy 18.96% drop. Meanwhile, non-revolving credit strutted upward from $1,646.2 trillion to $2,218.7 trillion, a 34.78% jump. Translation: people stopped swiping plastic and started signing their lives away on loans.

But here’s the kicker: student loans ballooned by $483.3 billion. That’s right, the future workforce financed their education with IOUs so massive they could power a small moon. Auto loans? A measly $84.6 billion. Personal loans? Practically pocket change at $4.6 billion. Strip out the student debt, and you’re left with a net reduction of over $100 billion. So much for “recovery”—it’s more like a magic trick where the rabbit is replaced by a tuition bill.

And yes, this is the “not seasonally adjusted” data, because apparently the Fed doesn’t bother to track motor vehicle loans in the “seasonally adjusted” version. Translation: even the spreadsheets are confused.

Oh, and let’s not forget the cherry on top: the article “How the Fed fueled an explosion in subprime auto loans.” Because nothing says “economic healing” like handing out car loans to people who can’t afford the gas.

At car dealers across the United States, loans to subprime borrowers like Nelson are surging - up 18 percent in 2012 from a year earlier, to 6.6 million borrowers, according to credit-reporting agency Equifax Inc. And as a Reuters review of court records shows, subprime auto lenders are showing up in a lot of personal bankruptcy filings, too.

The Fed swears that QE was all about juicing credit and pumping up consumption. Noble goal, right? Or was it? Maybe at first, but let’s be honest—the real game now is the so-called “wealth effect,” otherwise known as “make the stock market look shiny so everyone feels rich while eating ramen.”

Does it matter which excuse they use? Not really. Either way, the plan has flopped harder than a reality TV spin-off.

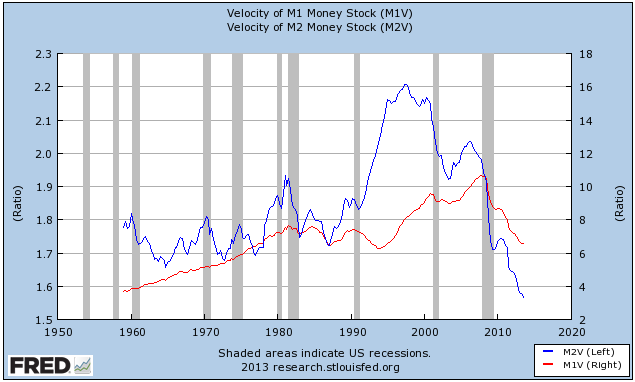

Ah yes, velocity of money—the chart that basically screams, “Nobody’s spending, everyone’s hoarding cash like it’s canned beans before Y2K.” No PhD required to see deflation and weak activity are the trendiest fashions of the season.

Credit cards? Don’t worry, they’re not going anywhere. They’ll be “reintroduced” to some wide-eyed generation down the road with the same tired promise: this time will be different. Spoiler alert: it won’t. Sure, debt for a house or car within strict affordability rules is the necessary evil we all nod along to. But financing a $50,000 car when you can only afford a $25,000 one? That’s not economics, that’s masochism. It props up today’s GDP but eventually kills the goose, the eggs, and probably the farmer too.

And what happens when the music stops? Cue 2007: default, reset, restructure. The trifecta of financial hangovers that leave scars deep enough to shape a generation’s spending habits. Meanwhile, corporations keep chasing revenue like it’s oxygen, leaning hard on financed consumption because apparently selling stuff people can’t afford is the business model of the century.

Older generations try to warn the newbies, but memories don’t transfer like USB files. The kids nod politely, then march straight into the same mistakes, chanting the eternal mantra: this time is different. Spoiler alert again: it isn’t.

Irving Fisher saw this coming way back in 1933 with his “Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions.” He never met a credit card, but he nailed the consequences of debt. His insights are still painfully relevant, and anyone searching for that mythical “economic magic bean” better bring a telescope—because it’s hiding somewhere past Pluto.

There may be equilibrium which, though stable, is so delicately poised that, after departure from it beyond certain limits, instability ensues, just as, at first, a stick may bend under strain, ready all the time to bend back, until a certain point is reached, when it breaks. This simile probably applies when a debtor gets “broke," or when the breaking of many debtors constitutes a “crash,” after which there is no coming back to the original equilibrium. To take another simile, such a disaster is somewhat like the “capsizing” of a ship which, under ordinary conditions, is always near stable equilibrium but which, after being tipped beyond a certain angle, has no longer this tendency to return to equilibrium, but, instead, a tendency to depart further from it.

“Tendency to depart further from it.” Oh, absolutely. Revolving credit has basically turned into humanity’s favorite time machine—perpetual consumption of the future. And as it shrinks, the ripple effect is still rolling in; the last wave hasn’t even hit shore yet. Meanwhile, Roubini casually suggests we “finance private consumption” like it’s a yoga mantra, ignoring the obvious: the buyer always ends up poorer, lugging around the debt like a bad gym membership.

Credit, in all its twisted forms, has become the deviant cornerstone of the U.S. economy—and by extension, the world. Add in government debt that grows faster than weeds, serviced by higher taxes, austerity, or both, and voilà: we’re building a mansion on a cracked foundation.

Robert Shiller once asked if economics is a science. Cute question. I’d argue it’s more like astrology with spreadsheets: inputs and outputs driven by human behavior, minus any real grasp of the behavior itself. And let’s not forget—most economic theories were written before credit cards even existed, so they’re about as prepared for modern debt dynamics as a caveman with a checkbook. Maybe black swans aren’t so rare; maybe they’re just badly disguised ducks.

Of course, everyone wants to know the stock market’s mood swings in advance. Between 1929 and 2001 we had 72 years of suspense. Here’s a fun fact: the Dow peaked at 381.17 in 1929, and bottomed at 6,547.05 in 2009. Adjust for inflation—$12.55 in 2009 equals $1 in 1929—and that low was worth 521.68 in 1929 dollars. Translation: after 80 years, we were only 37% above the 1929 high. That’s not progress, that’s a cosmic joke.

Price isn’t the guide; events are. And the market’s most advertised superpower—“discounting the future”—is basically gospel without proof. In reality, perceptions and emotions run the show. The market is myopic, blind to the ocean-sized currents beneath it, and when the mask of beauty slips, it doesn’t just frown—it morphs into a beast and thrashes violently.